Building a new graphics engine in Rust - Part 4

29 April 2023

Work has been continuing smoothly on my Rust graphics engine project hotline over the last month or so. I was slowly winding down from my current day job and have a little time off before starting a new role, so that has given me more time to dedicate to this project. I have been focusing on implementing different graphics demos and rendering techniques, which has thrown up a few missing pieces in the gfx backend and I am keen to get the API as complete as possible, because I am unsure of how much time I will have to work on it when I start my new role or even the validity of working on code in the public domain.

Tests

I started out the project building unit tests of graphics functionality and had those hooked up to run locally or on a self-hosted GitHub Actions runner. As the project progressed I encountered some issues with the tests crashing or being unable to run when launched within the plugin environment. I have a nice system of being able to switch between demos or in their current form they serve more as unit tests or examples, so I had been able to quickly, yet manually, run through the different examples to check things were all in good shape after making changes or refactoring. But still, automation is better and I was missing that support and comfort it can bring. I needed to resolve a crash inside my imgui backend where font glyph ranges passed to cimgui were actually pointing to dropped memory - this issue never seemed to crop up in debug or release builds and only in the tests, so it went undiagnosed for a while. The fix for this was fairly straightforward; just ensuring the memory remained in scope for when it was used.

Another issue with test running was that only one application can lock / use a dynamic library at a time, otherwise libloading will panic. Rust tests are launched and run asynchronously over multiple threads, so for the time being I have to run with -- -test-threads=1. This also helps with graphics related code because spawning 36+ Direct3D12 devices simultaneously is not possible and causes some of the tests to panic early on - failure to create a device is just a hard panic and there is no error handling. I suppose in this case I could wait and re-try and have some system there to at least allow some multithreading, but for the time being I am happy with the setup.

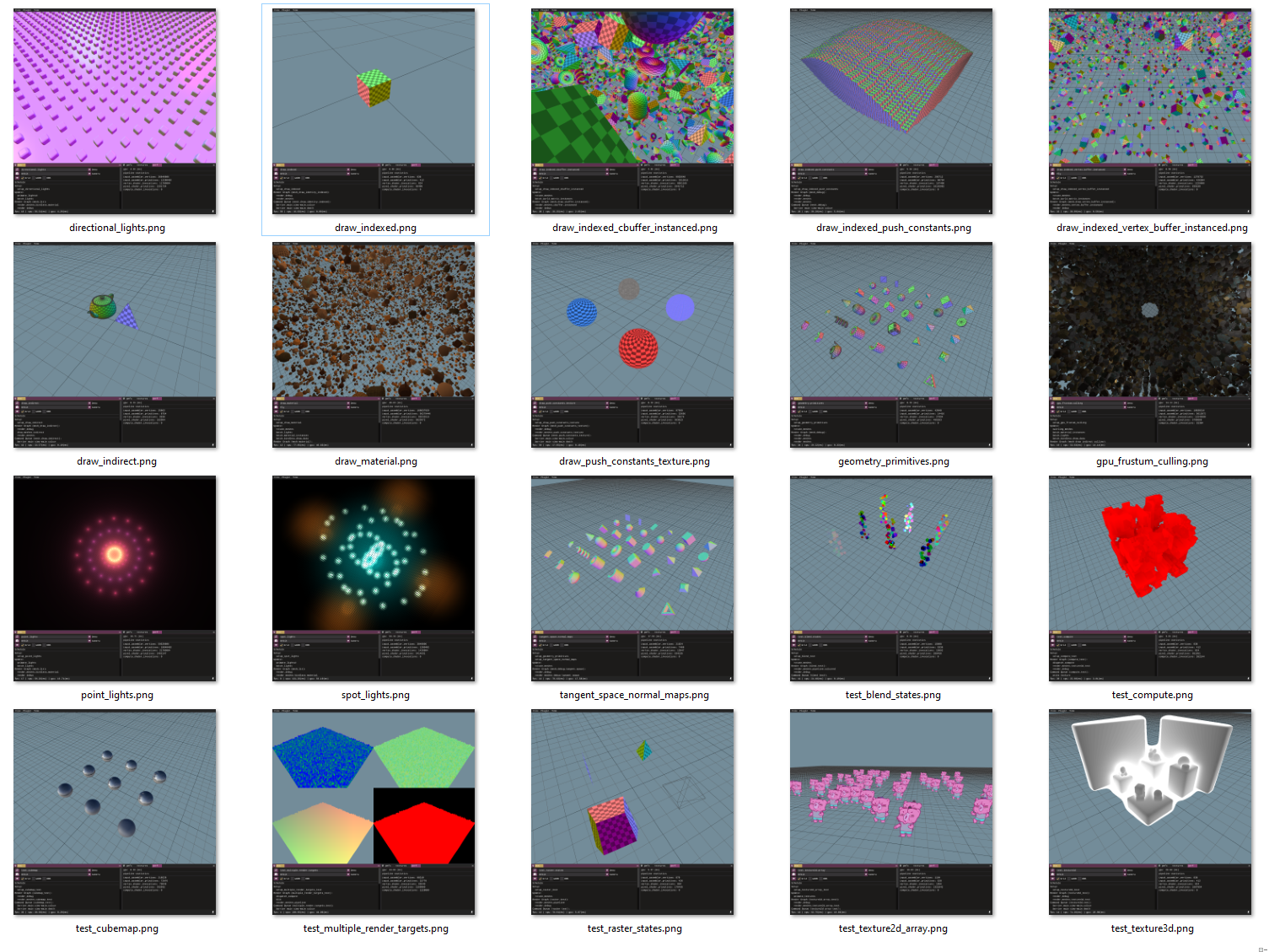

I also added support for each of the tests to take a grab of the backbuffer and write it to disk. I am not doing any kind of image detection on the images to automate pass or failure (currently if the test doesn’t panic or crash is enough to succeed) but having the images is a nice way to just glance and manually verify that everything looks correct.

Having these tests in place makes making changes or refactoring the lower level API’s easier and allows me to move quickly and confidently, which is exactly what I needed. They also run on the CI every time a commit is pushed and that helps to catch regressions where the shader data and the code become out of sync.

Hotline Data

With the tests in place I have made a few refactors and additions to the gfx API backend and I used the tests to aid this process. In my previous post I mentioned that I created a separate data repository to keep the main repository size down because crates.io has a 10mb limit. I originally created the hotline-data repository and used cargo to clone and update it on a build, so that the examples would still work whether using them from crates.io or GitHub. I actually decided against this and opted that the examples would work when using the repository direct from GitHub, and that if you decide to use the library from crates.io then you would configure data yourself for your own project. This subtle change enabled me to use hotline-data as a submodule and as a result that makes it easier to keep the data and the main repository in sync.

In the process of adding new graphics features I have had to make additions and changes to pmfx-shader. It comes bundled as a binary with the hotline-data repository, but while developing I switch to a development version which is actually written in python. Because things are moving quickly I have been frequently encountering new issues and switching to development mode. Now with the submodules and the tests this is helping to catch cases where I push to the repository with pmfx-shader in dev mode, so that I can quickly fix it and keep the repository in a state where it is buildable for new users at all times.

Dropping GPU Resources

I have previously mentioned challenges involving memory lifetime management between Rust and in-flight GPU resources, but I recently decided to bite the bullet and start handling these issues in the Drop trait for gfx::Texture and gfx::Buffer. I originally wanted to steer clear of this because it creates a dependency from a resource type to a gfx::Heap or a gfx::Device and then that in turn also throws in multithreaded considerations. I wanted to keep the low-level backend as simple and as dumb as possible, however from a user facing point of view it’s just too easy to run into serious problems such as a GPU hang / device removal (due to dropping an in-flight resource) or leaking views in heaps. This is because dropping a resource is very easy in Rust, you can simply allow a gfx::Texture or gfx::Buffer to go out of scope or assign a new one to a mutable variable.

The problem of dropping GPU resources started to rear its ugly head and force my hand as I started setting up some more complicated examples that were loading many textures. When switching between demos, textures were dropped as the bevy_ecs world was reset to default, but the associated shader resource views were not de-allocated from the shader heap. I also had issues with stretchy buffer types that resize like a vector for pushing in debug draw lines, or for light data and draw data in the bindless setup. When resizing, the previous smaller buffer would still be in-flight on the GPU and just dropping in place would lead to undefined behaviour. So this is where I really re-evaluated my thinking, just coming from a user perspective it’s a lot to think about and easy to fall into the trap.

In order to handle this I decided to just go for the full blown Arc<Mutex> wrapped around a DropList inside a gfx::Heap. All resources upon creation are assigned an Arc<Mutex<DropList>> to their respective heap and inside the Drop trait their resource views are added to the DropList. In future I would like to consider a lockless approach, but as I have done for the rest of the project I am focusing on stability first and the Mutex approach has worked well so far. In order to take ownership and add to the DropList the members inside a resource have now become Option’s so it’s possible to trivially std::mem::swap them, which is not great for the code elsewhere but it was a necessary change. I did try to just hack it and make a null version of an ID3D12_RESOURCE but this internally ends up causing a crash in windows-rs where a v-table is expected so the optional approach felt necessary. It adds some clutter in the backend, which was admittedly rushed, but that’s the price you pay for stability I suppose. When a resource is dropped the resource itself, any subresources (used for MSAA resolves), and any resource views are passed into the DropList owned by a heap:

/// Structure to track resources and resoure view allocations in `Drop` traits

struct DropResource {

resources: Vec<ID3D12Resource>,

frame: usize,

heap_allocs: Vec<usize>

}

struct DropList {

list: Mutex<Vec<DropResource>>

}

/// Thread safe ref counted drop-list that can be safely used in drop traits,

/// tracks the frame a resource was dropped on so it can be waited on

type DropListRef = std::sync::Arc<DropList>;

impl DropList {

fn new() -> std::sync::Arc<DropList> {

std::sync::Arc::new(DropList {

list: Mutex::new(Vec::new())

})

}

}

/// Drop trait for a texture resource

impl Drop for Texture {

fn drop(&mut self) {

/// Compile time const allows this feature to be omitted

if MANAGE_DROPS {

// only grab resources if we have a drop list, this allows the swap chain rtv

// to manage itself

let mut res_vec = if self.drop_list.is_some() {

// swap out the resources for None

let mut res = None;

std::mem::swap(&mut res, &mut self.resource);

let mut res_vec = vec![

res.unwrap()

];

if self.resolved_resource.is_some() {

let mut res = None;

std::mem::swap(&mut res, &mut self.resolved_resource);

res_vec.push(res.unwrap());

}

res_vec

}

else {

Vec::new()

};

// texture resource views

if let Some(drop_list) = &self.drop_list {

/// Add resources to the drop list

let mut drop_list = drop_list.list.lock().unwrap();

let mut drop_res = DropResource {

resources: res_vec.to_vec(),

frame: 0,

heap_allocs: Vec::new()

};

res_vec.clear();

/// Add resource views to the drop list

if let Some(srv_index) = self.srv_index {

drop_res.heap_allocs.push(srv_index);

}

if let Some(uav_index) = self.uav_index {

drop_res.heap_allocs.push(uav_index);

}

if let Some(resolved_srv) = self.resolved_srv_index {

drop_res.heap_allocs.push(resolved_srv);

}

drop_list.push(drop_res);

}

}

}

}

/// Since we now need to make resources `Options` and this adds extra baggage in the code elsewhere

//

let desc = unsafe { target.resource.as_ref().unwrap().GetDesc() }; // as ref, unwrap

//

let barrier = if let Some(tex) = &barrier.texture {

transition_barrier(

tex.resource.as_ref().unwrap(),

// ..

)

}

We need to manually sweep and clean things up. This step is out of line with Rust’s memory model but we need to synchronise the delete with the swap chain to ensure that any remaining references are complete on the GPU. So at the end of each frame we have a little bit of housekeeping to do where we can check the current frame number vs the frame in which the resource was dropped. To avoid a dependency on the SwapChain during the Drop itself, the frame index is initialised to zero and it is set the first time we call cleanup. The cleanup code will finally drop internal Direct3D12 resources when safe and then add the associated resource views in heaps onto a FreeList so the handles can be recycled when a new allocation is made.

fn cleanup_dropped_resources(&mut self, swap_chain: &SwapChain) {

/// lock drop list so it's thread safe

let mut drop_list = self.drop_list.list.lock().unwrap();

let mut free_list = self.free_list.list.lock().unwrap();

let mut complete_indices = Vec::new();

for (res_index, drop_res) in drop_list.iter_mut().enumerate() {

// initialise the frame, and then wait

if drop_res.frame == 0 {

drop_res.frame = swap_chain.frame_index;

}

else {

let diff = swap_chain.frame_index - drop_res.frame;

if diff > swap_chain.num_bb as usize {

// waited long enough we can add the resource views to the free list

for alloc in &drop_res.heap_allocs {

free_list.push(*alloc);

}

drop_res.resources.clear();

drop_res.heap_allocs.clear();

complete_indices.push(res_index);

}

}

}

// remove complete items in reverse

complete_indices.reverse();

for i in complete_indices {

drop_list.remove(i);

}

}

// call clean up at the end of each frame, this could be deferred or ran at different times

pub fn run(mut self) -> Result<(), super::Error> {

// ..

// cleanup heaps

self.pmfx.shader_heap.cleanup_dropped_resources(&self.swap_chain);

self.device.cleanup_dropped_resources(&self.swap_chain)

}

I would note that now at this point the gfx::Texture struct has become a chunky 148 bytes (not just from the extra requirements for Drop but also subresource management, render targets, depth stencils etc). It’s not something I am super keen on, but since we pass around only usize shader resource handles to reference textures in a shader, the texture struct itself can be a heavyweight resource and won’t likely be required during ecs iterators and such; it’s more like you create it once and just keep a hold of it so the memory remains in scope while it is used on the GPU.

#[derive(Clone)]

pub struct Texture {

resource: Option<ID3D12Resource>,

resolved_resource: Option<ID3D12Resource>,

resolved_format: DXGI_FORMAT,

rtv: Option<TextureTarget>,

dsv: Option<TextureTarget>,

srv_index: Option<usize>,

resolved_srv_index: Option<usize>,

uav_index: Option<usize>,

subresource_uav_index: Vec<usize>,

shared_handle: Option<HANDLE>,

// drop list for srv, uav and resolved srv

drop_list: Option<DropListRef>,

// the id of the shader heap for (uav, srv etc)

shader_heap_id: Option<u16>

}

I did consider a mechanism to pass a reference to a command buffer, so that dropping a reference to a texture wouldn’t actually drop the internal resource, but in a bindless rendering setup this becomes a lot harder to track. You are just indexing into descriptor arrays on the GPU and you don’t have to physically bind anything like in a bindful rendering architecture, so I am happy with the drop trait handling for the time being. Still, I can foresee a lot of potential pitfalls but it’s a step in the right direction.

Resource Heaps

Initially I tried to abstract away the Heap concept for speed of development - by keeping a Heap as part of a Device this allows the ability to call device.create_texture() in a Direct3D11 kind of way. I still like this approach for quick demos and noodling around, but it became clear as more complexity began to emerge in the higher level pmfx library and entity component system that it would be a benefit to be able to create and manage your own heaps. This would allow the heaps to be dynamically resized and resources could be re-allocated or moved; an entire heap could be thrown away between levels in a game or switching between projects. I decided to allow both methods by having the following set of functions.

// Create buffer and create texture will add resource views into an internally managed heap owned by the device

fn create_buffer<T: Sized>(

&mut self,

info: &BufferInfo,

data: Option<&[T]>,

) -> Result<Self::Buffer, Error>;

fn create_texture<T: Sized>(

&mut self,

info: &TextureInfo,

data: Option<&[T]>,

) -> Result<Self::Texture, Error>;

// pass a heap to create buffer resoruce views on a user managed heap

fn create_buffer_with_heap<T: Sized>(

&mut self,

info: &BufferInfo,

data: Option<&[T]>,

heap: &mut Self::Heap

) -> Result<Self::Buffer, Error>;

// textures might require multiple heaps, you can provide your own or use the device managed heaps with None

pub struct TextureHeapInfo<'stack, D: Device> {

/// Heap to allocate shader resource views and un-ordered access views

pub shader: Option<&'stack mut D::Heap>,

/// Heap to allocate render target views

pub render_target: Option<&'stack mut D::Heap>,

/// Heap to allocate depth stencil views

pub depth_stencil: Option<&'stack mut D::Heap>,

}

// create texture with user managed heaps

fn create_texture_with_heaps<T: Sized>(

&mut self,

info: &TextureInfo,

heaps: TextureHeapInfo<Self>,

data: Option<&[T]>,

) -> Result<Self::Texture, Error>;

This allows for maximum flexibility, providing low level control where you need it or simpler ergonomics when you don’t.

ImGui Image Rendering With Multiple Heaps

Allowing user specified heaps threw up problems with imgui image rendering. Because now a Texture may reside in different heaps, a simple call to imgui.image(texture) did not provide enough context. Previously I was relying on only a single program-wide shader resource heap that was internally managed by the gfx::Device. Some data still resides in said heap, this is true for the imgui font texture, so I needed a way to pass this information around. Luckily due to the changes in dropping GPU resources I had more information contained in a gfx::Texture I could use at my disposal. Imgui images work by passing around a void* for a ImTextureID. Now, with Rust lifetimes I did not want to make this a full blown reference because simply all we need is the shader resource view handle, which is stored as a usize. The handles are allocated linearly inside a gfx::Heap and managed with a free list, so having a full range of 64-bits for shader resource handles is more than enough, even 32-bits is probably excessive. Each gfx::Heap gets allocated an ID and the ID’s are assigned sequentially upon creation, so I took the approach of packing the shader resource view handle and heap id together into 64-bits. 16 upper bits represent the heap id and the lower 48 represent the shader resource view handle. When passing a texture to imgui.image this process is handled for you, and then when we come to render imgui we just need to provide a vector of any additional user heaps.

// pass an array of heap references to imgui render. empty vector will use the device heap only

pub fn render(

&mut self,

app: &mut A,

main_window: &mut A::Window,

device: &mut D,

cmd: &mut D::CmdBuf,

image_heaps: &Vec<&D::Heap>,

)

// code to unpack the 16bit heap id and 48bit srv id

fn to_srv_heap_id(tex_id: *mut cty::c_void) -> (usize, u16) {

let mask = 0x0000ffffffffffff;

let srv_id = (tex_id as u64) & mask;

let heap_id = ((tex_id as u64) & !mask) >> 48;

(srv_id as usize, heap_id as u16)

}

fn render_draw_data() {

// ..

// extract srv and heap id from the packed texture id

let (srv, heap_id) = to_srv_heap_id(imgui_cmd.TextureId);

if heap_id == device.get_shader_heap().get_heap_id() {

// bind the device heap

cmd.set_binding(pipeline, device.get_shader_heap(), 1, srv);

}

else {

// bund srv in another heap

for heap in image_heaps {

if heap.get_heap_id() == heap_id {

cmd.set_binding(pipeline, heap, 1, srv);

break;

}

}

}

}

There is more than enough prevision in the 48 and 16 bits for any sane use-cases so I began to think I could also pack some extra info in there as well, maybe the texture type and render flags could be easily packed into 8-bits to allow changing shaders and rendering textures differently through imgui. This would open the opportunity to provide a more fully featured texture viewer, with alpha masking or different kinds of controls. I had implemented something similar before using custom callbacks, but I didn’t really like the overall architecture and just packing data into the ImTextureID is much nicer. But that’s something on the backburner for another day.

GPU-Hangs

I started to encounter intermittent, random GPU hangs and device removals as I began to add more complicated examples. When these occurred I would get misleading call stacks from crashes occurring during the stack unwind and no D3D12 validation errors or messages. I spent a while trying to pin down the problem in an old school fashion; commenting out code and simplifying, but I could never quite put my finger on what exactly was going on. In one particular example that had bindless draw, material, and light data lookups, with a fair amount of indirection in there it would sometimes crash on startup, but not all the time. Once the sample had booted it was stable. Other hangs would occur on some basic examples, but only when switching between. It was like the first frame would be intermittently unstable or not, and if you got past that then it would be OK. I verified my indices coming into the shaders and I did resolve a few things that looked like they might be the cause, but ended up being red-herrings, these were namely some out-of-order updates where render calls were being made before updates.

This sort of problem is really annoying to search for on the internet. Just searching for DXGI_DEVICE_HUNG throws up search results from various commercial games, with users on reddit and steam complaining about their games not working. Just so much clutter with useless info (update your drivers, get a new GPU). I wanted some developer focused information! I managed to find some forum posts on gamedev that mentioned EnableGPUValidation this can be enabled on a D312Debug1 interface:

// enable debug layer

let mut dxgi_factory_flags: u32 = 0;

if cfg!(debug_assertions) {

let mut debug: Option<D3D12DebugVersion> = None;

if let Some(debug) = D3D12GetDebugInterface(&mut debug).ok().and(debug) {

debug.EnableDebugLayer();

// slower but more detailed GPU validation

if GPU_VALIDATION {

let debug1 : ID3D12Debug1 = debug.cast().unwrap();

debug1.SetEnableGPUBasedValidation(true);

}

println!("hotline_rs::gfx::d3d12: enabling debug layer");

}

dxgi_factory_flags = DXGI_CREATE_FACTORY_DEBUG;

}

I was able to reproduce the hangs after a few attempts and got some debug output, progress!

D3D12 ERROR: GPU-BASED VALIDATION: Draw, Uninitialized root argument accessed. Shader Stage: VERTEX,

Root Parameter Index: [3], Draw Index: [0], Shader Code: <couldn't find file location in debug info>,

Asm Instruction Range: [0xd-0xffffffff], Asm Operand Index: [0],

Command List: 0x00000232EE9CC450:'Unnamed ID3D12GraphicsCommandList Object',

SRV/UAV/CBV Descriptor Heap: 0x00000232EDB1C3C0:'Unnamed ID3D12DescriptorHeap Object',

Sampler Descriptor Heap: <not set>, Pipeline State: 0x0000023299DFCB30:'Unnamed ID3D12PipelineState Object',

[ EXECUTION ERROR #935: GPU_BASED_VALIDATION_ROOT_ARGUMENT_UNINITIALIZED]

At this point I was happy, I don’t mind something being wrong, especially if there is some validation telling me it’s wrong. It gives me the opportunity to work with it and fix the validation and then the symptoms. I do feel stressed if I am encountering a problem with no errors, warnings or validation messages. This makes me feel like I’m straying into territory of broken hardware or drivers which may be harder to work around, although having said that, in my experience such issues account for an extremely small percentage of problems I have encountered in my life as a programmer, and almost all issues I have ever faced have been self inflicted.

This validation error brought me back to shader registers, spaces, and root parameter indices. My original code was grouping all descriptor ranges by visibility and then creating a root parameter per shader visibility, which I go into more detail in the next section, but while I am here on the topic of GPU hangs / device removals I encountered another problem that did not have any validation output.

The cause of the issue came from population IndirectArgument unordered access buffers on the GPU as part of a GPU driven rendering setup. It took a while to track down because of the lack of information, but thanks to the useful size and alignment hints supplied by vscode I was able to notice that the size of the indirect argument structure was larger than expected - some padding was being added at the end. For all structures in use on the GPU I was using #[repr(C)] and I thought this would be enough to prevent this kind of problem, but in the end I needed to change to #[repr(packed) to prevent any padding being added.

// size = 72, align = 8

#[repr(C)]

pub struct DrawIndirectArgs {

pub vertex_buffer: gfx::VertexBufferView,

pub index_buffer: gfx::IndexBufferView,

pub ids: Vec4u,

pub args: gfx::DrawIndexedArguments,

}

// size = 68, align = 1

#[repr(packed)]

pub struct DrawIndirectArgs {

pub vertex_buffer: gfx::VertexBufferView,

pub index_buffer: gfx::IndexBufferView,

pub ids: Vec4u,

pub args: gfx::DrawIndexedArguments,

}

Bindless Rendering

I had done some initial exploratory work into bindless rendering in the very early stages of this project, but recently I started needing more data accessible on the GPU and that began to highlight changes that needed to be made both from a functionality point of view but also a usability perspective. With the aforementioned GPU hangs being caused by the bindless setup I started to look into that in more detail. The naming around this aspect of modern graphics api’s is quite confusing, it’s different in Vulkan and Metal and I don’t find Descriptors, RootSignatures or RootConstants very intuitive names to begin with. Since I had worked with Vulkan first I stuck with PipelineLayout, Descriptors and PushConstants. I did have to do a little backtracking here just to make sure everything was consistently named and in the context of this post I hope the concepts are clear enough to follow. A PipelineLayout describes Descriptors, PushConstants and Samplers that are used in the pipeline where Descriptors are arrays of resources such as textures, structured buffers, or constant buffers. PushConstants are a small amount of data that we can push into the command buffer on the CPU to have access to in a shader, and Samplers are used to sample textures and are the only part of all of this that has a sense of familiarity with older graphics APIs.

PipelineLayouts are automatically generated by my shader system pmfx-shader. Based on resource usage in shaders and a small amount of metadata, the pmfx-shader system is able to parse the code and automatically generate the layout. Binding heaps and push constants can be a little confusing because in the shader we specify which register and space we bind them to, and in the old days of bindful rendering, we would bind a texture onto the designated register or slot as I often would call them. I discovered that even with different registers or spaces the binding slot or ‘root parameter index’ (as Direct3D12 calls it) might not be as expected due to the auto-generated layout from pmfx-shader. Direct3D12 allows multiple descriptor ranges to be bound to the same slot; I am not sure the benefit of grouping more descriptors onto the same slot or keeping them separate, but they do need to be at the very least grouped by shader visibility, which is one of Vertex, Fragment, Compute etc or All of it is to be bound and accessible on multiple stages.

/// `PipelineLayout` is required to create a pipeline it describes the layout of resources for access on the GPU.

#[derive(Default, Clone, Serialize, Deserialize)]

pub struct PipelineLayout {

/// Vector of `DescriptorBinding` which are arrays of textures, samplers or structured buffers, etc

pub bindings: Option<Vec<DescriptorBinding>>,

/// Small amounts of data that can be pushed into a command buffer and available as data in shaders

pub push_constants: Option<Vec<PushConstantInfo>>,

/// Static samplers that come along with the pipeline,

pub static_samplers: Option<Vec<SamplerBinding>>,

}

I toyed with a few implementations first, all of which felt cumbersome and I read through the msdn docs about bindings, multiple times and that took more than a while to sink in. In an attempt to make this as simple as possible for the user you can supply a vector of descriptors when creating a PipelineLayout. Under the hood the descriptors are grouped by type (srv, uav, cbv), register and shader visibility. This gives unique slots for different types of resources and opens the door to a bindful rendering model where it may be useful.

The key takeaway in regards to bindless rendering was that we bind a heap separately and then we can apply offsets within that heap to the different slots in the pipeline, but critically we can only bind a single descriptor heap at any one time. So in the context of a bindless rendering architecture we only have a single heap we use at any time and that contains all of our resources. Equipped with this knowledge it made it easy for me to add a utility function that would bind the heap for all of the slots, which need access to Descriptors… I still feel uncomfortable calling them descriptors, and still confused. I often refer to them as shader resources myself, but anyway. A quick example of how the code evolved over time:

fn render(cmd_buf: &gfx::CmdBuf, shader_heap: &gfx::Heap) {

// 1. initially you would bind the heap on to the pipeline slot manually...

cmd_buf.set_render_heap(1, shader_heap);

// you would also have a separate function for compute

cmd_buf.set_compute_heap(1, shader_heap);

// and would need to bind to multiple slots

cmd_buf.set_render_heap(2, shader_heap);

cmd_buf.set_render_heap(3, shader_heap);

cmd_buf.set_render_heap(4, shader_heap);

// 2. I then added a utility so we know which slot is associated with a particular register

let slot = pipeline.get_pipeline_slot(0, 0, gfx::DescriptorType::ShaderResource);

if let Some(slot) = slot {

cmd_buf.set_render_heap(slot.index, shader_heap);

}

/// this still required multiple binds

let slot = pipeline.get_pipeline_slot(1, 0, gfx::DescriptorType::ShaderResource);

if let Some(slot) = slot {

cmd_buf.set_render_heap(slot.index, shader_heap);

}

// 3. moved to a single set_heap call with generics for compute and render pipelines

pass.cmd_buf.set_heap(render_pipeline, &pmfx.shader_heap);

//

pass.cmd_buf.set_heap(compute_pipeline, &pmfx.shader_heap);

}

Bindful Rendering

It is still useful sometimes to revert to a ‘bindful’ render model, the imgui backend code is doing this since the shader itself only uses a single texture and the ImTextureID is passed through code as previously discussed. I was also using this similar approach in a blit function that just needed access to a single texture. Here I added a utility function that can be used to obtain a PipelineSlot based on the register, space, and type of resource. An offset into the heap can then be applied to the PipelineSlot. The offset is supplied by obtaining a texture or buffers srv_index or uav_index; these can be used to bind the heap at an offset and essentially they become the same as an old-school Direct3D11 style renderer.

// set the heap

pass.cmd_buf.set_heap(pipeline, &pmfx.shader_heap);

// find the slot and bind the offset

let slot = pipeline.get_pipeline_slot(1, 0, gfx::DescriptorType::ShaderResource);

if let Some(slot) = slot {

view.cmd_buf.set_binding(pipeline, &pmfx.shader_heap, slot.index, srv as usize);

}

The PipelineSlot API can also be used to get the correct location of push constants, again looking them up by register and space from the shader. The return value is optional so that it makes it possible to re-use shared code and only bind certain constants if a shader requires them. For example, some shaders may need push constants for the view matrix as well as an object world matrix, but some shaders may only need one or the other.

// bind view push constants

let slot = pipeline.get_pipeline_slot(0, 0, gfx::DescriptorType::PushConstants);

if let Some(slot) = slot {

view.cmd_buf.push_render_constants(slot.index, 16, 0, gfx::as_u8_slice(&camera.view_projection_matrix));

view.cmd_buf.push_render_constants(slot.index, 4, 16, gfx::as_u8_slice(&camera.view_position));

}

// bind the world buffer info

let world_buffer_info = pmfx.get_world_buffer_info();

let slot = pipeline.get_pipeline_slot(2, 0, gfx::DescriptorType::PushConstants);

if let Some(slot) = slot {

view.cmd_buf.push_render_constants(

slot.index, gfx::num_32bit_constants(&world_buffer_info), 0, gfx::as_u8_slice(&world_buffer_info));

}

GPU-Driven Rendering

In addition to the bindless architecture, I intend the final core ecs architecture to be GPU driven. GPU driven rendering allows command buffers to be populated on the GPU and this offloads CPU intensive work. This is where graphics APIs diverge quite significantly, so for this stage I am focusing on what is possible in Direct3D12 but I do have one eye on compatibility for other platforms. There is a nice detailed post on the webgpu issues page that outlines differences between graphics APIs. I had also had some prior experience with Metal as well so the concepts are relatively familiar. In short, Metal allows you to build entire command buffers on the GPU; Direct3D12 allows you to change a binding (vertex, index or descriptor), change push constants and draw arguments, but you can’t change pipelines; Vulkan allows you only to change draw arguments… that is without any extensions.

I will cross the bridge of cross platform support when I come to it, but in its current form hotline offers support for execute_indirect just as Direct3D12 does. I made a few samples to trial this:

// populate a buffer of draw arguments

let args = gfx::DrawArguments {

vertex_count_per_instance: 3,

instance_count: 1,

start_vertex_location: 0,

start_instance_location: 0

};

// create an INDIRECT_ARGUMENT_BUFFER

let draw_args = device.create_buffer(&gfx::BufferInfo{

usage: gfx::BufferUsage::INDIRECT_ARGUMENT_BUFFER,

cpu_access: gfx::CpuAccessFlags::NONE,

format: gfx::Format::Unknown,

stride: std::mem::size_of::<gfx::DrawArguments>(),

initial_state: gfx::ResourceState::IndirectArgument,

num_elements: 1

}, hotline_rs::data!(gfx::as_u8_slice(&args))).unwrap();

// create a command signature

let command_signature = device.create_indirect_render_command::<gfx::DrawArguments>(

vec![gfx::IndirectArgument{

argument_type: gfx::IndirectArgumentType::Draw,

arguments: None

}],

None

).unwrap();

// bind buffers and make the execute indirect call

view.cmd_buf.push_render_constants(1, 12, 0, &world_matrix.0);

view.cmd_buf.set_index_buffer(&mesh.0.ib);

view.cmd_buf.set_vertex_buffer(&mesh.0.vb, 0);

view.cmd_buf.execute_indirect(

&command.0,

1,

&args.0,

0,

None,

0

);

GPU Entity Frustum Culling

I set up a basic example with a large number of draw calls being submitted from the CPU to see how switching to execute_indirect would fare. The initial implementation loaded 32k entities with 30 unique meshes randomly selected, so the vertex and index buffers needed changing each draw call, with a single pipeline used for all meshes. This clocked in heavily CPU bound at about 80ms per-frame with no culling being performed what-so-ever.

Setting up for execute_indirect is fairly straightforward. The whole thing starts off with a buffer created on the CPU containing all of the draw arguments and buffer indices for each entity we want to draw. Then we create an unordered access buffer that the draw arguments will be copied into dynamically for only visible entities, after culling them on the GPU. Here it uses an AppendStructuredBuffer in the shader; this is a type not present in Metal shader language or GLSL, so in future I will have to implement some system to get the same behaviour, but essentially it consists of a buffer for data with a space in the buffer to store an atomic counter, which is incremented as we append items into the buffer. We can pass this counter to the execute_indirect call so it knows how many entities to draw.

// command signature specifies we change vertex and index buffers and update 2 push constants

let command_signature = device.create_indirect_render_command::<DrawIndirectArgs>(

vec![

gfx::IndirectArgument{

argument_type: gfx::IndirectArgumentType::VertexBuffer,

arguments: Some(gfx::IndirectTypeArguments {

buffer: gfx::IndirectBufferArguments {

slot: 0

}

})

},

gfx::IndirectArgument{

argument_type: gfx::IndirectArgumentType::IndexBuffer,

arguments: None

},

gfx::IndirectArgument{

argument_type: gfx::IndirectArgumentType::PushConstants,

arguments: Some(gfx::IndirectTypeArguments {

push_constants: gfx::IndirectPushConstantsArguments {

slot: pipeline.get_pipeline_slot(1, 0, gfx::DescriptorType::PushConstants).unwrap().slot,

offset: 0,

num_values: 4

}

})

},

gfx::IndirectArgument{

argument_type: gfx::IndirectArgumentType::DrawIndexed,

arguments: None

}

],

Some(pipeline)

).unwrap();

// buffer is populated with draw call information for all entities

// read data from the arg_buffer in compute shader to generate the `dynamic_buffer`

let arg_buffer = device.create_buffer_with_heap(&gfx::BufferInfo{

usage: gfx::BufferUsage::SHADER_RESOURCE,

cpu_access: gfx::CpuAccessFlags::NONE,

format: gfx::Format::Unknown,

stride: std::mem::size_of::<DrawIndirectArgs>(),

initial_state: gfx::ResourceState::IndirectArgument,

num_elements: indirect_args.len()

}, hotline_rs::data!(&indirect_args), &mut pmfx.shader_heap).unwrap();

// append buffer created to copy visible entities into

// dynamic buffer has a counter packed at the end

let dynamic_buffer = device.create_buffer_with_heap(&gfx::BufferInfo{

usage: gfx::BufferUsage::INDIRECT_ARGUMENT_BUFFER | gfx::BufferUsage::UNORDERED_ACCESS | gfx::BufferUsage::APPEND_COUNTER,

cpu_access: gfx::CpuAccessFlags::NONE,

format: gfx::Format::Unknown,

stride: std::mem::size_of::<DrawIndirectArgs>(),

initial_state: gfx::ResourceState::IndirectArgument,

num_elements: indirect_args.len(),

}, hotline_rs::data![], &mut pmfx.shader_heap).unwrap();

// create a buffer with 0, so we can clear the counter each frame by copy buffer region

let counter_reset = device.create_buffer_with_heap(&gfx::BufferInfo{

usage: gfx::BufferUsage::NONE,

cpu_access: gfx::CpuAccessFlags::NONE,

format: gfx::Format::Unknown,

stride: std::mem::size_of::<u32>(),

initial_state: gfx::ResourceState::CopySrc,

num_elements: 1,

}, hotline_rs::data![gfx::as_u8_slice(&0)], &mut pmfx.shader_heap).unwrap();

fn render() {

// reset the counter

let offset = indirect_draw.dynamic_buffer.get_counter_offset().unwrap();

pass.cmd_buf.copy_buffer_region(&indirect_draw.dynamic_buffer, offset, &indirect_draw.counter_reset, 0, std::mem::size_of::<u32>());

// transition to `UnorderedAccess`

pass.cmd_buf.transition_barrier(&gfx::TransitionBarrier {

texture: None,

buffer: Some(&indirect_draw.dynamic_buffer),

state_before: gfx::ResourceState::CopyDst,

state_after: gfx::ResourceState::UnorderedAccess,

});

// dispatch compute job to perform culling

pass.cmd_buf.dispatch(

gfx::Size3 {

x: indirect_draw.max_count / pass.numthreads.x,

y: pass.numthreads.y,

z: pass.numthreads.z

},

pass.numthreads

);

// transition to `IndirectArgument`

pass.cmd_buf.transition_barrier(&gfx::TransitionBarrier {

texture: None,

buffer: Some(&indirect_draw.dynamic_buffer),

state_before: gfx::ResourceState::UnorderedAccess,

state_after: gfx::ResourceState::IndirectArgument,

});

// draw indirect

view.cmd_buf.execute_indirect(

&indirect_draw.signature,

indirect_draw.max_count,

&indirect_draw.dynamic_buffer,

0,

Some(&indirect_draw.dynamic_buffer),

indirect_draw.dynamic_buffer.get_counter_offset().unwrap()

);

}

In the shader we use bindless lookups to obtain the entities extents data, camera planes, and perform a test against each plane in the frustum to detect whether an entity is inside or not. If the entity is visible, its draw data is copied into the indirect argument buffer and the counter is incremented.

struct indirect_draw {

buffer_view vb;

buffer_view ib;

uint4 ids;

draw_indexed_args args;

};

// potential draw calls we want to make

StructuredBuffer<indirect_draw> input_draws[] : register(t0, space11);

// draw calls to populate during the `cs_frustum_cull` dispatch

AppendStructuredBuffer<indirect_draw> output_draws[] : register(u0, space0);

bool aabb_vs_frustum(float3 aabb_pos, float3 aabb_extent, float4 planes[6]) {

bool inside = true;

for (int p = 0; p < 6; ++p) {

float3 sign_flip = sign(planes[p].xyz) * -1.0f;

float pd = planes[p].w;

float d2 = dot(aabb_pos + aabb_extent * sign_flip, planes[p].xyz);

if (d2 > -pd) {

inside = false;

}

}

return inside;

}

[numthreads(128, 1, 1)]

void cs_frustum_cull(uint did : SV_DispatchThreadID) {

// grab entity draw data

extent_data extents = get_extent_data(did);

camera_data main_camera = get_camera_data();

// grab potential draw call

indirect_draw input = input_draws[resources.input1.index][did];

if(aabb_vs_frustum(extents.pos, extents.extent, main_camera.planes)) {

output_draws[resources.input0.index].Append(input);

}

}

The plane culling code is some old code from my C++ code base, it was implemented following this excellent article from ryg.

Switching from regular draw_indexed calls to draw_indirect improves the CPU time significantly (80ms to 16ms with v-sync) and the GPU time also drops due to the decreased vertex workload. I was able to then increase the number of entities and get the same performance. I did notice then that the program still remains CPU bound with higher draw or entity counts - this is due to the entities positions, world matrices, and bounds being updated on the CPU. More of this work could be offloaded to the GPU and there can also be consideration to manage static vs dynamic objects differently. There seems to be some increased CPU overhead with larger draw counts in execute_indirect I want to also investigate the difference in performance of indirect draw indexed vs draw indexed instanced.

There is still more research to do in this area. I don’t have a GPU that supports mesh shaders yet so I am still investigating what is possible without such luxuries, but I think instanced execute_indirect calls will be helpful and some triangle / cluster level culling could also be added for large meshes, I can see a few possible in-roads there without the need for mesh shaders. But while that stuff sits in the back of my mind, putting all of this together leads to the next section.

Bindless / GPU Driven Entity Component System

With the bindless setup and GPU driven examples in mind, some structure started to form for how these systems will be driven by entities in the entity component system. Across the various samples the following data is required for access on the GPU.

- per-entity draw data (world matrix).

- per-entity bounds / entents data for GPU culling.

- material data (texture ids, colours, material parameters).

- light data (positions, colours, attenuation factors).

- camera data (projection matrices, view positions).

This data can be stored in StructuredBuffers and updated each frame. The pmfx system creates a set of WorldBuffers which is essentially a structure of arrays containing a DynamicBuffer, which is a structured buffer that can grow and stretch like a vector. I am using persistently mapped buffers to make updates to the GPU and multi-buffering the internals so each frame we write to a back buffer while the front buffer can be read on the GPU. The world buffers contains the following:

pub struct DynamicWorldBuffers<D: gfx::Device> {

/// Structured buffer containing bindless draw call information `DrawData`

pub draw: DynamicBuffer<D, DrawData>,

/// Structured buffer containing bindless draw call information `DrawData`

pub extent: DynamicBuffer<D, ExtentData>,

// Structured buffer containing `MaterialData`

pub material: DynamicBuffer<D, MaterialData>,

// Structured buffer containing `PointLightData`

pub point_light: DynamicBuffer<D, PointLightData>,

// Structured buffer containing `SpotLightData`

pub spot_light: DynamicBuffer<D, SpotLightData>,

// Structured buffer containing `DirectionalLightData`

pub directional_light: DynamicBuffer<D, DirectionalLightData>,

/// Constant buffer containing camera info

pub camera: DynamicBuffer<D, CameraData>

}

In the shader code we have these un-bounded bindless arrays of different resource types which all alias the same register but sit in a different space.

// structures of arrays for indriect / bindless lookups

StructuredBuffer<draw_data> draws[] : register(t0, space0);

StructuredBuffer<extent_data> extents[] : register(t0, space1);

StructuredBuffer<material_data> materials[] : register(t0, space2);

StructuredBuffer<point_light_data> point_lights[] : register(t0, space3);

StructuredBuffer<spot_light_data> spot_lights[] : register(t0, space4);

StructuredBuffer<directional_light_data> directional_lights[] : register(t0, space5);

// textures

Texture2D textures[] : register(t0, space6);

Texture2DMS<float4, 8> msaa8x_textures[] : register(t0, space7);

TextureCube cubemaps[] : register(t0, space8);

Texture2DArray texture_arrays[] : register(t0, space9);

Texture3D volume_textures[] : register(t0, space10);

All resources go into the same gfx::Heap. I call this the shader_heap and it contains textures of all kinds as well as structured buffers. We can then use indices to look up the information we need on the GPU. Some things like materials can have 2 levels of indirection (first lookup the material by ID and then lookup textures by ID provided by the material). Depending on how draw calls are made, this information may come from different sources and I have explored a few different strategies I will cover later in this post, but for the simplest approach let’s just say that per draw call, we use PushConstants for each entity to push, and we need to push some constants that can tell us the id’s of each of the world buffers. The WorldBuffersInfo struct contains a pair of uint’s - one to identify the location of the buffer and one to notify the length of the buffer so we can loop over n lights and also offers some opportunity to perform some range checks. In the context of execute_indirect the id’s of the draw and material buffers are pushed through as part of the indirect draw arguments.

// bind view push constants

let slot = pipeline.get_pipeline_slot(0, 0, gfx::DescriptorType::PushConstants);

if let Some(slot) = slot {

view.cmd_buf.push_render_constants(slot.slot, 16, 0, gfx::as_u8_slice(&camera.view_projection_matrix));

view.cmd_buf.push_render_constants(slot.slot, 4, 16, gfx::as_u8_slice(&camera.view_position));

}

// bind the world buffer info

let world_buffer_info = pmfx.get_world_buffer_info();

let slot = pipeline.get_pipeline_slot(2, 0, gfx::DescriptorType::PushConstants);

if let Some(slot) = slot {

view.cmd_buf.push_render_constants(

slot.slot, gfx::num_32bit_constants(&world_buffer_info), 0, gfx::as_u8_slice(&world_buffer_info));

}

// bind the shader resource heap

view.cmd_buf.set_heap(pipeline, &pmfx.shader_heap);

Now in any shader we can look up the WorldBuffers and get a particular draw, material, or light data. I made some utility functions to assist this process which also makes the lookups more readable.

// get entity world matrix based on entity id

draw_data draw = get_draw_data(entity_input.ids[0]);

// get entity material based on id

material_data mat = get_material_data(entity_input.ids[1]);

// lookup lights and loop over

uint point_lights_id = world_buffer_info.point_light.x;

uint point_lights_count = world_buffer_info.point_light.y;

if(point_lights_id != 0) {

int i = 0;

for(i = 0; i < point_lights_count; ++i) {

point_light_data light = point_lights[point_lights_id][i];

// ..

}

}

Compute Passes

The main scene scene can be rendered through render systems and driven by the bevy_ecs scheduler and I have now added support to provide compute passes inside .pmfx configs, which can be dispatched automatically or hooked into their own function if some custom code is required. I intend to do all post-processing through compute shaders and completely abandon rasterization post-processing. If all data required by a compute shader is supplied in a .pmfx config, it is very quick and easy to integrate new compute passes to the frame’s render graph:

textures: {

compute_texture3d: {

width: 64,

height: 64,

depth: 64,

usage: [UnorderedAccess, ShaderResource]

}

}

pipelines: {

compute_write_texture3d: {

cs: cs_write_texture3d

push_constants: [

resources

]

}

}

render_graphs: {

compute_test(base): {

write_texture: {

function: "dispatch_compute"

pipelines: ["compute_write_texture3d"]

uses: [

["compute_texture3d", "Write"]

]

target_dimension: "compute_texture3d"

}

}

}

Bindless rendering again makes light work of the configuration because all textures and buffers we might want to use will already be allocated inside a heap, and each resource will have appropriate views setup based on usage flags supplied during creation. The only thing we need to know is the index of the resource view we wish to access a resource through. Resource usages can be specified in the .pmfx config, and you can also notify the target resource dimensions (the one which you are writing to) so that on the code size the group size can be automatically worked out.

textures: {

gbuffer_albedo: {

ratio: {

window: main_dock

scale: 1.0

}

format: RGBA16f

usage: ["ShaderResource", "RenderTarget"]

samples: 8

}

gbuffer_normal(gbuffer_albedo): {}

gbuffer_position(gbuffer_albedo): {}

gbuffer_depth(gbuffer_albedo): {

format: D24nS8u

usage: ["ShaderResource", "DepthStencil"]

}

}

render_graphs: {

multiple_render_targets_test: {

meshes: {

view: "heightmap_mrt_view"

pipelines: [

"heightmap_mrt"

]

function: "render_meshes_pipeline"

}

resolve_mrt: {

function: "dispatch_compute"

pipelines: ["heightmap_mrt_resolve"]

uses: [

["staging_output", "Write"]

["gbuffer_albedo", "ReadMsaa"]

["gbuffer_normal", "ReadMsaa"]

["gbuffer_position", "ReadMsaa"]

["gbuffer_depth", "ReadMsaa"]

]

target_dimension: "staging_output"

depends_on: ["meshes"]

}

}

}

This data is packed together with the resource dimensions, which are also sometimes useful to be able to lookup in the shader for sampling coordinates and so forth.

/// To lookup resources in a shader, these are passed to compute shaders:

/// index = srv (read), uav (write)

/// dimension is the resource dimension where 2d textures will be (w, h, 1) and 3d will be (w, h, d)

#[repr(C)]

pub struct ResourceUse {

pub index: u32,

pub dimension: Vec3u

}

/// Resoure uage for a graph pass

#[derive(Serialize, Deserialize, Clone)]

enum ResourceUsage {

/// Write to an un-ordeded access resource or rneder target resource

Write,

/// Read from the primary (resovled) resource

Read,

/// Read from an MSAA resource

ReadMsaa

}

// pass the resource usage indices as push constants

let using_slot = pipeline.get_pipeline_slot(0, 0, gfx::DescriptorType::PushConstants);

if let Some(slot) = using_slot {

for i in 0..pass.use_indices.len() {

let num_constants = gfx::num_32bit_constants(&pass.use_indices[i]);

pass.cmd_buf.push_compute_constants(

0,

num_constants,

i as u32 * num_constants,

gfx::as_u8_slice(&pass.use_indices[i])

);

}

}

struct resource_use {

uint index;

uint3 dimension;

}

struct resource_uses {

resource_use input0;

resource_use input1;

resource_use input2;

resource_use input3;

resource_use input4;

resource_use input5;

resource_use input6;

resource_use input7;

}

ConstantBuffer<resource_uses> resources: register(b0);

[numthreads(8, 8, 8)]

void cs_write_texture3d(uint3 did : SV_DispatchThreadID) {

// ..

rw_volume_textures[resources.input0.index][did.xyz] = float4(nn, 0.0, 0.0, nn < 0.9 ? 0.0 : 1.0);

}

For simple compute passes there may be no need for a user to specify any additional data, so the resource usage information is automatically bound and the compute shader is dispatched automatically. This, in addition to being able to write multiple resources at the same time from a shader, and the opportunity to single pass jobs vs multi-pass ping-pong approaches as seen in raster based systems, is very appealing. I have yet to write any proper post-processes but the infrastructure is now in place.

It might be necessary to drive more complex compute workflows with scene data, which is evident in the GPU driven frustum culling example. Here, instead of having the compute shader automatically dispatched, you can supply a custom function that gets passed the useful aforementioned data (resource usage info, dimensions etc).

#[no_mangle]

pub fn dispatch_compute_frustum_cull(

pmfx: &Res<PmfxRes>,

pass: &mut pmfx::ComputePass<gfx_platform::Device>,

indirect_draw_query: Query<&DrawIndirectComponent>)

-> Result<(), hotline_rs::Error> {

// custom code to setup compute pipelines

// ..

pass.cmd_buf.dispatch(

gfx::Size3 {

x: indirect_draw.max_count / pass.numthreads.x,

y: pass.numthreads.y,

z: pass.numthreads.z

},

pass.numthreads

);

}

After doing a few simple compute examples I was surprised not to see any Direct3D12 validation warnings or errors regarding resource states and prompts to insert transition barriers. At first I thought, ‘great’ it might not be something I need to worry about, but after using the GPU based validation I mentioned earlier to diagnose some GPU hangs, I noticed that there were some validation warnings spewing out in the console. Everything works fine so I haven’t tackled it yet, but having the validation messages to notify is very useful, and with the resource usage information in compute passes and also in render passes, the pmfx system will be able to automatically insert barriers as I am already doing for render target to shader resource, MSAA resolves and mip-map generation…

Generate Mip Maps

Direct3D11 and Metal provide mechanisms to generate mip-maps for textures at run time but Direct3D12 has no such inbuilt functionality. Generating mips for textures such as render targets can be quite useful so I added a quick utility to do this. It consists of a built-in compute shader which can perform the downsample iteratively. I initially tried to make a single pass downsample and had some reasonable results, but I put it on hold for the time being as it was taking longer than I initially anticipated. The internal implementation can be changed at a later time, here I just wanted to make sure the API was nice and easy to use. A gfx::Texture can be created with various flags, internally it may create multiple resources and resource views based on flags. You can create a textures that allows run time mip-map generation and a similar process is also followed for MSAA resolves:

// create texture with usage GENERATE_MIP_MAPS

let info = gfx::TextureInfo {

width,

height,

tex_type,

initial_state,

usage | gfx::TextureUsage::GENERATE_MIP_MAPS,

mip_levels,

depth: pmfx_texture.depth,

array_layers: pmfx_texture.array_layers,

samples: pmfx_texture.samples,

format: pmfx_texture.format,

}

// create texture with heap

let tex = device.create_texture_with_heaps::<u8>(

&info,

gfx::TextureHeapInfo {

shader: heap,

..Default::default()

},

None

)?;

// resolve texture

cmd_buf.resolve_texture_subresource(tex, 0)?;

// generte mips for texture

cmd_buf.generate_mip_maps(tex, device, device.get_shader_heap())?;

Graphics Examples

I have completed a relatively comprehensive set of graphics examples which demonstrate and test the implemented features of the hotline API’s all integrated and using the entity component system kindly provided by bevy_ecs. Some of these examples are pretty basic and I am leaving them there for test purposes and to aid future work porting the engine to different platforms. Along the way I have been using these to explore different rendering techniques and get a rough idea of performance and will ultimately decide on a final architecture that will be used under the hood by the ecs. This final architecture is starting to take shape but I will do a quick run-down of the examples I have implemented so far. I went into more detail in previous post about how the ecs works, but the gist of it is that you supply setup, update, and render functions that are bevy_ecs systems and then a render_graph supplied in a pmfx config file. More information about each of the graphics examples can be found in the hotline GitHub repository.

Next Up

I am going to continue researching into GPU-Driven rendering techniques and hopefully start creating some more advanced looking demos. I hope you enjoyed this post, if you did you can follow the social links on my website for more content on whichever platforms you use.